Abstract

Children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) with rigidities, anxiety or sensory preferences may establish a pattern of holding urine and stool, which places them at high risk of developing bladder bowel dysfunction (BBD). BBD, despite being common, is often unrecognised in children with ASD. With this case report of a 7-year-old girl with ASD presenting with acute retention of urine, we attempt to understand the underlying factors which may contribute to the association between BBD and ASD. Literature review indicates a complex interplay of factors such as brain connectivity changes, maturational delay of bladder function, cognitive rigidities and psychosocial stressors in children with ASD may possibly trigger events which predispose some of them to develop BBD. Simple strategies such as parental education, maintaining a bladder bowel diary and treatment of constipation may result in resolution of symptoms.

Keywords: paediatrics, developmental paediatrics

Background

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder which affects approximately 1 in 59 children in the USA,1 and 31.4% have intellectual disability (ID). Anxiety is a common comorbidity. Bladder bowel dysfunction (BBD) is frequently seen in children diagnosed with neurodevelopmental disorders, particularly ASD and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).2 3 Limited studies look into this association.

BBD in typically developing children

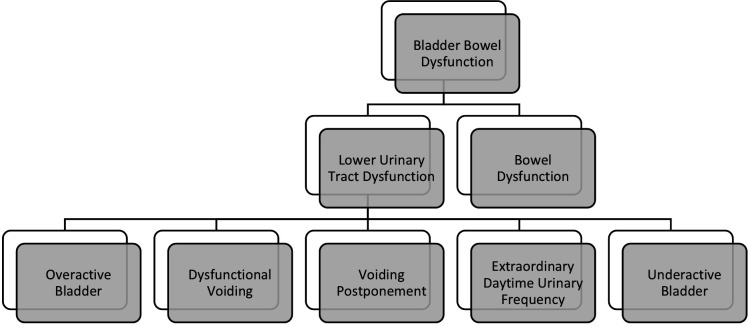

BBD may be defined as a spectrum of urological conditions presenting with lower urinary tract symptoms accompanied by constipation and/or encopresis.4 These are described in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Bladder bowel dysfunction subtypes.

BBD represents up to 40% of paediatric urology consults.5–7 Although the cause of BBD is multifactorial, non-biological factors including stressful life events, such as parental separation and abuse, have been associated with BBD.8–11

Among the various subtypes of functional lower urinary tract disorders comprising BBD, dysfunctional voiding (DV) is associated with the most comorbidity.12 DV results when the external urethral sphincter-pelvic floor complex fails to relax appropriately during voiding, resulting in obstructed micturition, in the absence of any neuroanatomical abnormality.13 DV typically occurs after toilet training and before puberty, with consequential recurrent urinary tract infections (UTIs), urinary incontinence, voiding difficulties, unexplained urinary retention or urethral/suprapubic pain.

BBD in children with ASD

Children with ASD are more at risk of DV and enuresis than healthy controls.14 Up to 24.3% of children with a confirmed diagnosis of ASD have some type of incontinence.15 16 Disrupted brain connectivity changes affecting areas involved in bladder control, together with higher rates of ID, sleep problems or psychiatric comorbidity (eg, anxiety), predispose them to a higher risk of BBD.17 18

Additionally, the phenotypic attributes of cognitive rigidities, sensory preferences and communication difficulties may help maintain cycles of voiding postponement for prolonged periods. This may establish a pattern where they exhibit reduced sensation to evacuate, resulting in lower urinary symptoms with constipation and/or encopresis. Attention and activity problems are common in children with ASD, which may also be linked to a ‘reduced sensation to evacuate’ and children ignoring bladder and bowel signals due to focusing on other activities.4 19 20 Overtraining of the pelvic floor in an attempt to encourage to stay dry may also lead to increased intravesical pressures and increased postvoid residual volumes, especially in those with ID.21

Among those with comorbid ID, inability to achieve toilet training milestones may be attributed to maturational delay. Hence, BBD symptoms may often go unnoticed.

Among typically developing children, prospective studies which looked into specific child and parent behaviours during the toilet training process (such as withholding manoeuvres, constipation and hiding) concluded that factors such as age at initiation of toilet training, constipation and development of stool toileting refusal partially explained why some children completed toilet training later than others.22 23 The authors recommended that the paediatrician actively intervene when there is lack of successful toilet training by 42 months of age and/or stool withholding is causing constipation, which can result in rectal impaction and primary encopresis. A child who is still untrained at this late age can be a source of family conflict and stress, requiring the advice and support of the paediatrician.

Furthermore, while studies have shown that delaying the onset of toilet training until after 2 years of age prolongs the exposure time to potential stressors that can interfere with acquisition of bladder control, we have limited data to guide us on the most opportune time of toilet training in children with developmental delay.24 The American Academy of Pediatrics does not give any set age at which toilet training should commence and recommends that it depend on a child’s level of physical and psychological maturation.

When taking into account the need to establish and maintain continence for children with ASD and other developmental disabilities, it is especially important to consider individual characteristics associated with toileting competence.25 The same principles of treatment used in typically developing children can be applied in children with ASD, provided that their restrictive behavioural patterns, sensory preferences, communication and motor problems, their comorbid disorders, and their cognitive level are taken into consideration.3 14 25–30 By using specific behavioural techniques such as visual schedules and picture cards which may capitalise on their strength in learning via visual presentation, providing toilet routine and rewards, reducing sensory overload, and addressing coexisting medical and psychological concerns, many children with ASD can be toilet-trained effectively.31 A literature review by Kroeger and Sorensen-Burnworth25 describes the following behavioural components of toilet training programmes for individuals with ASD and other developmental disabilities: graduated guidance inclusive of prompting, reinforcement-based training, scheduled sittings, elimination schedules, hydration, manipulation of stimulus control and cognitive behavioural method of priming and video modelling. Graduated guidance, using a prompting hierarchy with the least intrusive, minimal prompt to elicit the target behaviour in a chain of behaviours (undressing, voiding, redressing, flushing and washing hands), and scheduled sitting are some of the most frequently used behavioural components.26 30 Scheduled sitting is a procedure where individuals are placed on (or in front of, depending on sex and training protocol) the toilet and then positively reinforced when voiding occurs. These were often used along with hydration procedures, providing individuals with highly preferred and large volume of liquids. Associated risks related to excessive water intake should be monitored.26 30 32 Introducing scheduled chair sittings as another step in scheduled toilet sitting may be helpful for those who have difficulty initiating trips to the toilet. A chair is placed near the toilet (about 2 feet away) and prompts may be used for bringing the child from the chair to the toilet when he or she initiates voiding and does not move from the chair to the toilet. The chair may be moved farther away as the child begins to eliminate without prompts.33 34

Another strategy using elimination schedules identifies and records an individual’s pattern of voiding frequency and timing using mechanical devices and manual detection using dry and wet checks.26 30 35 Reinforcement-based trainings provide positive reinforcement (such as a preferred edible or activity) after a successful void and negative reinforcement (in the form of response restriction where participants were restricted from making any response incompatible with appropriate toileting behaviours when in the toilet vicinity) and are often used in conjunction with other strategies.30 36 These strategies allow successful implementation without the use of punishment procedures. Literature also reports the use of manipulated stimulus control in addition to the established protocol in those children resistant to toilet training. It involves analysing the controlling antecedent stimulus for accidents and gradually changing the antecedent behaviours using the findings of the individual’s tendencies to void outside the toilet.37

Among children with ASD, with their relative strengths in visual spatial domains, development of toileting skills may be facilitated by use of cognitive behavioural methods of priming and video modelling.38 39 Video modelling has been reported as one of the novel advances since the last review in 2009.40–42 Priming provides information using a toilet training video before the behaviour is completed in order to increase the likelihood of the behaviour being completed.38 Keen et al39 used animated video and picture cards in conjunction with operant conditioning principles. The toilet training video shows the sequence of toileting steps required by both boys and girls in a simple and logical order, making use of sound, colour and interesting and friendly characters. Animated characters provide simple verbal instructions. Praise is given for appropriate toileting. A set of A4 picture cue cards accompanies the video. These strategies, by minimising attention and language demands, will also be effective in children with developmental delay and associated comorbidities like ADHD.39 They also reported that frequency of in-toilet urinations increased when a child was afforded greater privacy when sitting on the toilet and when picture cue cards were used to redirect the child away from areas where inappropriate urinations were occurring. They emphasised the importance of understanding how changes in the child’s routine, such as illness, change of caregivers and change in medication, may cause regression in toilet training. It would be helpful if caregivers were made aware of the impact of these changes and provided support. Patience, persistence, consistency across settings and access to a support person with whom they could problem-solve, as well as privacy and relaxation for the child, were reported by caregivers as important factors in promoting successful toilet training.39

Urodynamic investigations in children with ASD

More pathological flows indicative of incomplete or dysfunctional bladder emptying were seen in ASD during urological examinations.15 These patterns may suggest an immaturity of the bladder function, such as seen in neonatal voiding. Resolution of this pattern in a typically developing child occurs by the time of toilet training.43 Artefacts on a uroflowmetry due to anxiety in children with ASD towards any beeping sounds or unfamiliar procedures should also not be overlooked.15

Incontinence in ASD due to medication

Incontinence rates after medication onset were reported at 1% for melatonin44 and 3.2%–65.4% for risperidone.45 46 Other medications implicated include guanfacine, aripiprazole and levetiracetam.

Case presentation

Child A was initially seen at a specialised developmental clinic at the age of 3 years and 2 months with language delay, behavioural concerns and feeding issues.

She was physically well and was born at term. The Ages and Stages Questionnaire indicated delayed communication, problem-solving and personal social skills. Her mother described her refusing to eat particular foods for certain periods of time. Caregivers also had difficulty managing her tantrums. She was referred for speech-language therapy and subsequently enrolled in a preschool with integrated early intervention.

Her language assessment indicated moderate deficits in receptive and expressive language, with lack of gesture use and delayed pretend play skills. She underwent a psychological assessment at the age of 5 years and 5 months, which confirmed ASD and mild ID. At 7 years of age, she started attending a special education school.

Besides social communication difficulties, her behavioural profile revealed rigidity and a compulsive adherence to routines. Toy figurines, her coin bank and the telephone had to be aligned a particular way at home. She became pickier about the food she ate, mainly eating noodles and soup, and was rigid about the sequence in which she ate food. Her fluid intake was limited, usually not exceeding 1 L per day.

Rigid behaviours also existed around her toileting habits. She would insist to have her diaper on all the time and would withhold urine for periods of up to 4 hours otherwise. She was unable to spontaneously inform caregivers if her diaper was wet, although she could respond if they asked her so. Conversely, she was able to indicate the urge to pass stool and had been using the toilet successfully for this since she was 3.5 years old. However, she refused to use public toilets and would withhold stool in school to defecate at home. As a result, she had chronic constipation, which was managed with a phosphate enema up to three times a month from when she was 2 years old. There was no history of UTIs.

In view of her developmental delays, caregivers had not been very persistent in getting her toilet-trained for passing urine. After starting special school, however, they started to take her to the toilet up to five to six times daily. She was also required to sit on the toilet bowl with a diaper on and practise deep breathing, a strategy improvised by her mother to improve toilet usage.

At 7 years and 4 months, child A presented to the paediatric emergency department (ED) with abdominal pain. She had acute retention of urine (ARU) for the preceding 8 hours. No apparent triggers were identified. The only change in her regular routine before the ARU was that she had started fasting for the first time for Ramadan 2 days previously.

Investigations and treatment

At the ED, an in-out catheterisation was performed, a phosphate enema administered and she was admitted for further investigations. A renal panel, urine microscopy and culture, ultrasound of the abdomen/pelvis and MRI of the lumbosacral spine were all normal. No underlying neurological dysfunction was identified. During her 3-day inpatient stay, she had two more episodes of ARU lasting up to 20 hours, with associated lower abdominal pain. The second episode was managed with another in-out catheterisation and the third episode with an indwelling urinary catheter (IDC).

Following IDC insertion, she was reviewed by the urology team and advised for a period of ‘bladder rest’ with the urinary catheter in situ. She was discharged with advice on catheter care, charting fluid balance and maintaining regular bowel habits. Four days after the IDC was inserted, she returned to the urology clinic for a trial off catheter (TOC). Four hours after the TOC, a bladder scan indicated 400 mL of urine, which was above her estimated bladder capacity of 240 mL. She experienced suprapubic discomfort and reported the urge to pass urine but was unable to void. Hence, an IDC was reinserted. There was no faecal loading on an abdominal X-ray that day. A decision was made to rest the bladder for a longer period of time in view of possible bladder atony secondary to the recurrent episodes of ARU.

Two weeks later, after undergoing bladder training via intermittent IDC clamping for 3 days, two further TOCs in clinic and at home were again unsuccessful. Bladder scans indicated 300–400 mL residual 5 hours after TOC, and IDCs were reinserted.

The multiple failed attempts at TOC despite an overdistended bladder raised the possibility of neurogenic bladder. A urodynamic study was therefore arranged which indicated normal detrusor activity during filling and no detrusor activity during voiding. Failure to void with no detrusor contraction at bladder capacity was also observed.

The ideal recommended treatment would have been clean intermittent catheterisation. However, this was impossible for child A, as each catheter insertion was extremely distressing, with physical restraint often required. The interim plan was for monthly catheter change while on uroprophylaxis. The possibility of a suprapubic catheter insertion was also discussed with the family. Parent education on the treatment of constipation and bladder relaxation strategies was regularly conducted.

Outcome and follow-up

Two months after her first episode of ARU, child A was noted to be able to pass approximately 86 mL of concentrated urine spontaneously after a blocked IDC was removed. A postvoid bladder scan confirmed no residual urine. Caregivers requested for another TOC at home at this point. She was able to pass urine once at home but returned to the ED again later after not having passed urine for almost 6 hours. When she was coaxed to pass urine in a diaper before any IDC insertion was conducted, she finally succeeded and the diaper was soaked. A postvoid scan indicated no residual. She continued to be able to use the diaper to pass urine in. One month following the removal of the IDC, she spontaneously started asking caregivers to bring her to the toilet and would micturate once every 4–5 hours. Serial bladder scans to monitor postvoid urine volumes confirmed no residual urine.

Discussion

Retrospectively, there appears to be a pattern of events which ultimately resulted in ARU. The child’s cognitive rigidity with regard to her toileting habits helped maintain a pattern of withholding urine and stool, which predisposed her to BBD and perhaps gradually reduced the sensation to pass urine, resulting in infrequent voids. It is difficult to establish the onset of BBD because a bladder bowel diary was not maintained prior to her episode of ARU. Infrequent voiding and overflow incontinence could not be ruled out. Additional toilet training in the months immediately prior to Ramadan, followed by 2 days of fasting, possibly placed significant stress on the child and acted as triggers for the first ARU episode.

Diagnosis of BBD in children with ASD

Assessment

Initial evaluation should include a detailed parent and child interview, with medication history and screening for anxiety, cognitive rigidity and stressful life events. Family psychosocial screening to identify and address psychological problems in caregivers is important as they may affect treatment of their children.

Recommended urological assessment consists of physical examination, maintaining a bladder/bowel diary, ultrasonography and uroflowmetry.47 Voiding scores such as the Dysfunctional Voiding Score System and the Vancouver Symptom Score for Dysfunctional Elimination Syndrome, with modified versions using visual aids, may be useful for assessing current functioning and monitoring progress.48–50

Among children with suspected BBD, any underlying neuroanatomical dysfunction should be excluded. Investigations include baseline urinalysis and urine culture if there is evidence of infection. In boys, posterior urethral valves should be looked for. In the presence of lower limb neurological deficits, cutaneous lesions in the lumbosacral region or occult spinal dysraphism on an abdominal X-ray, an MRI of the spine or spinal ultrasound should be considered to rule out cord tethering and other neurogenic causes.

Uroflowmetry with pelvic electromyography followed by postvoid residual measurement is reserved for more severe cases. Medical investigations may need modification to reduce anxiety for children with ASD.

Management

The underlying principle for treatment of BBD is regular and complete emptying of the bladder and the rectum. Educational material in jargon-free language may be shared with parents even before the clinic visit to help start behaviour therapy at home and reduce parental stress. As the dysfunction is acquired, behaviour therapy should focus on retraining the child to relax the bladder outlet via urotherapy and biofeedback.4 Timed voiding, visual schedules and social stories may also help anxiety and cognitive rigidities towards toileting.

Along with bladder training, identification and treatment of bowel dysfunction are important.51 52 Studies have shown that treatment of constipation can result in 89% reduction in daytime wetting, 63% reduction in night-time wetting and prevention of UTIs.52

Pharmacotherapy such as anticholinergics, selective alpha blockers, and invasive procedures such as bladder botulin injection and sacral neuromodulation may be considered if there is no improvement with the aforementioned despite adequate compliance or for those whose renal status is at risk.12 In the presence of vesicoureteral reflux (VUR), prophylactic antibiotics should be considered. Collaborating with school nursing or home care teams, which may include sharing practical tips and toilet training guidelines, may result in a higher success for implementing the management plan.53–56 In one of the studies, among children with failure to toilet-train, group treatment involving both the child and the family resulted in greater improvement in toileting outcomes than individual treatment.53 Small studies showed intervention programmes implemented by school staff without clinic support have also been effective in successfully toilet-training children with ASD or developmental delays who demonstrated no prior success in the home or school setting. One of the studies focused on interventions that included removal of diapers during school hours, scheduled time intervals for bathroom visits, a maximum of 3 min sitting on the toilet, delivering reinforcers immediately on urination in the toilet, and gradually increased time intervals between bathroom visits as each participant met mastery during the preceding, shorter time interval.54

Providing anticipatory guidance and advice on fluid intake, diet and toileting patterns during routine clinic visits as well as collaborating with school staff, with provision for adjunctive parent/school staff training if needed, may be helpful in reducing the risk of BBD in the long term by setting an effective early intervention framework.

Learning points.

Children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) with rigidities, anxiety or sensory preferences may establish a pattern of holding urine and stool, which eventually reduces the physiological neural stimuli for evacuation, placing them at high risk of developing bladder bowel dysfunction (BBD).

Regular screening for BBD in children with ASD may help avoid chronic complications.

Behaviour therapy, with treatment of associated constipation, may improve BBD in most cases.

Providing anticipatory guidance and advice on fluid intake, diet and toileting patterns during routine clinic visits as well as collaborating with school staff may be helpful in reducing the risk of BBD in the long term.

Footnotes

Contributors: SR served as the primary author. She reviewed the case in detail, interviewed the mother and read all available reports on clinical progress and reports by the allied health professionals. She also performed a comprehensive literature review with regard to analysing the clinical findings and supporting the discussion. FXL played a key role in the discussion of the diagnosis and management of the patient and editing the case report. CMW revised multiple drafts of the case report and organised the information. She was also involved in the clinical discussion pertaining to the diagnostic challenges faced with the patient in question.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Baio J, Wiggins L, Christensen DL, et al. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years - autism and developmental aisabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2014. MMWR Surveill Summ 2018;67:1–23. 10.15585/mmwr.ss6706a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simonoff E, Pickles A, Charman T, et al. Psychiatric disorders in children with autism spectrum disorders: prevalence, comorbidity, and associated factors in a population-derived sample. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2008;47:921–9. 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318179964f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.von Gontard A. Urinary incontinence in children with special needs. Nat Rev Urol 2013;10:667–74. 10.1038/nrurol.2013.213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Santos JD, Lopes RI, Koyle MA. Bladder and bowel dysfunction in children: an update on the diagnosis and treatment of a common, but underdiagnosed pediatric problem. Can Urol Assoc J 2017;11:64–72. 10.5489/cuaj.4411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang R, Kanani R, El Bardisi Y, et al. Development of a standardized approach for the assessment of bowel and bladder dysfunction. Pediatr Qual Saf 2019;4:e144. 10.1097/pq9.0000000000000144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.dos Santos J, Varghese A, Koyle M. Recommendations for the management of bladder bowel dysfunction in children. Pediat Therapeut 2014;04:1. 10.4172/2161-0665.1000191 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Halachmi S, Farhat WA. Interactions of constipation, dysfunctional elimination syndrome, and vesicoureteral reflux. Adv Urol 2008;828275:828275. 10.1155/2008/828275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Logan BA, Correia K, McCarthy J, et al. Voiding dysfunction related to adverse childhood experiences and neuropsychiatric disorders. J Pediatr Urol 2014;10:634–8. 10.1016/j.jpurol.2014.06.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.von Gontard A. Does psychological stress affect LUT function in children? ICI-RS 2011. Neurourol Urodyn 2012;31:344–8. 10.1002/nau.22216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ellsworth PI, Merguerian PA, Copening ME. Sexual abuse: another causative factor in dysfunctional voiding. J Urol 1995;153:773–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wood SK, Baez MA, Bhatnagar S, et al. Social stress-induced bladder dysfunction: potential role of corticotropin-releasing factor. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2009;296:R1671–8. 10.1152/ajpregu.91013.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clothier JC, Wright AJ. Dysfunctional voiding: the importance of non-invasive urodynamics in diagnosis and treatment. Pediatr Nephrol 2018;33:381–94. 10.1007/s00467-017-3679-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chase J, Austin P, Hoebeke P, et al. The management of dysfunctional voiding in children: a report from the standardisation Committee of the International children's continence Society. J Urol 2010;183:1296–302. 10.1016/j.juro.2009.12.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.von Gontard A, Pirrung M, Niemczyk J, et al. Incontinence in children with autism spectrum disorder. J Pediatr Urol 2015;11:264.e1–7. 10.1016/j.jpurol.2015.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Niemczyk J, Fischer R, Wagner C, et al. Detailed assessment of incontinence, psychological problems and parental stress in children with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 2019;49:1966–75. 10.1007/s10803-019-03885-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Niemczyk J, Wagner C, von Gontard A. Incontinence in autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2018;27:1523–37. 10.1007/s00787-017-1062-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rane P, Cochran D, Hodge SM, et al. Connectivity in autism: a review of MRI connectivity studies. Harv Rev Psychiatry 2015;23:223–44. 10.1097/HRP.0000000000000072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fowler CJ, Griffiths DJ. A decade of functional brain imaging applied to bladder control. Neurourol Urodyn 2010;29:49–55. 10.1002/nau.20740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schast AP, Zderic SA, Richter M, et al. Quantifying demographic, urological and behavioral characteristics of children with lower urinary tract symptoms. J Pediatr Urol 2008;4:127–33. 10.1016/j.jpurol.2007.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duel BP, Steinberg-Epstein R, Hill M, et al. A survey of voiding dysfunction in children with attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder. J Urol 2003;170:1521–4. 10.1097/01.ju.0000091219.46560.7b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Handel LN, Barqawi A, Checa G, et al. Males with Down's syndrome and nonneurogenic neurogenic bladder. J Urol 2003;169:646–9. 10.1097/01.ju.0000047125.89679.28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taubman B. Toilet training and toileting refusal for stool only: a prospective study. Pediatrics 1997;99:54–8. 10.1542/peds.99.1.54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blum NJ, Taubman B, Osborne ML. Behavioral characteristics of children with stool toileting refusal. Pediatrics 1997;99:50–3. 10.1542/peds.99.1.50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Joinson C, Heron J, Von Gontard A, et al. A prospective study of age at initiation of toilet training and subsequent daytime bladder control in school-age children. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2009;30:385–93. 10.1097/dbp.0b013e3181ba0e77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kroeger KA, Sorensen-Burnworth R. Toilet training individuals with autism and other developmental disabilities: a critical review. Res Autism Spectr Disord 2009;3:607–18. 10.1016/j.rasd.2009.01.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.LeBlanc LA, Carr JE, Crossett SE, et al. Intensive outpatient behavioral treatment of primary urinary incontinence of children with autism. Focus Autism Other Dev Disabl 2005;20:98–105. 10.1177/10883576050200020601 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hanney NM, Jostad CM, Leblanc LA. Intensive behavioral treatment of urinary incontinence of children with autism spectrum disorders: an archival analysis of procedures and outcomes from an outpatient clinic. Focus Autism Other Dev Disabil 2013;28:26e31. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Henriksen N, Peterson S. Behavioral treatment of Bedwetting in an adolescent with autism. J Dev Phys Disabil 2013;25:313–23. 10.1007/s10882-012-9308-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.NICE . Guideline: autism. the management and support of children and young children on the autism spectrum, 2013. Available: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg170/resources/guidance-autism-pdf [Accessed 6 Aug 14].

- 30.Azrin NH, Foxx RM. A rapid method of toilet training the institutionalized retarded. J Appl Behav Anal 1971;4:89–99. 10.1901/jaba.1971.4-89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brown FJ, Peace N. Teaching a child with challenging behaviour to use the toilet: a clinical case study. Br J Learn Disabil 2011;39:321–6. 10.1111/j.1468-3156.2011.00676.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lott JD, Kroeger KA. Self-help skills in persons with mental retardation. : Matson JL, Laud RB, Matson ML, . Behavior modification for persons with developmental disabilities: treatment and supports (Vol. II). New York: National Association for the Dually Diagnosed, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rinald K, Mirenda P. Effectiveness of a modified rapid toilet training workshop for parents of children with developmental disabilities. Res Dev Disabil 2012;33:933–43. 10.1016/j.ridd.2012.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kroeger K, Sorensen R. A parent training model for toilet training children with autism. J Intellect Disabil Res 2010;54:556–67. 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2010.01286.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McLay L, Carnett A, van der Meer L, et al. Using a video modeling-based intervention package to toilet train two children with autism. J Dev Phys Disabil 2015;27:431–51. 10.1007/s10882-015-9426-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Averink M, Melein L, Duker PC. Establishing diurnal bladder control with the response restriction method: extended study on its effectiveness. Res Dev Disabil 2005;26:143–51. 10.1016/j.ridd.2004.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taylor S, Cipani E, Clardy A. A stimulus control technique for improving the efficacy of an established toilet training program. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry 1994;25:155–60. 10.1016/0005-7916(94)90010-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bainbridge N, Smith Myles B, Myles BS. The use of priming to introduce toilet training to a child with autism. Focus Autism Other Dev Disabl 1999;14:106–9. 10.1177/108835769901400206 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Keen D, Brannigan KL, Cuskelly M. Toilet training for children with autism: the effects of video modeling. J Dev Phys Disabil 2007;19:291–303. 10.1007/s10882-007-9044-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Francis K, Mannion A, Leader G. The assessment and treatment of toileting difficulties in individuals with autism spectrum disorder and other developmental disabilities. Rev J Autism Dev Disord 2017;4:190–204. 10.1007/s40489-017-0107-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee CYQ, Anderson A, Moore DW. Using video modeling to toilet train a child with autism. J Dev Phys Disabil 2014;26:123–34. 10.1007/s10882-013-9348-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Drysdale B, Lee CYQ, Anderson A, et al. Using video modeling incorporating animation to teach toileting to two children with autism spectrum disorder. J Dev Phys Disabil 2015;27:149–65. 10.1007/s10882-014-9405-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jansson U-B, Hanson M, Sillén U, et al. Voiding pattern and acquisition of bladder control from birth to age 6 years--a longitudinal study. J Urol 2005;174:289–93. 10.1097/01.ju.0000161216.45653.e3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Andersen IM, Kaczmarska J, McGrew SG, et al. Melatonin for insomnia in children with autism spectrum disorders. J Child Neurol 2008;23:482–5. 10.1177/0883073807309783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology Autism Network . Risperidone treatment of autistic disorder: longer-term benefits and blinded discontinuation after 6 months. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162:1361–9. 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.7.1361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aman MG, Arnold LE, McDougle CJ, et al. Acute and long-term safety and tolerability of risperidone in children with autism. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2005;15:869–84. 10.1089/cap.2005.15.869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Austin PF, Bauer SB, Bower W, et al. The standardization of terminology of lower urinary tract function in children and adolescents: update report from the standardization Committee of the International children's continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn 2016;35:471–81. 10.1002/nau.22751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Farhat W, Bägli DJ, Capolicchio G, et al. The dysfunctional voiding scoring system: quantitative standardization of dysfunctional voiding symptoms in children. J Urol 2000;164:1011–5. 10.1097/00005392-200009020-00023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Afshar K, Mirbagheri A, Scott H, et al. Development of a symptom score for dysfunctional elimination syndrome. J Urol 2009;182:1939–43. 10.1016/j.juro.2009.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Drzewiecki BA, Thomas JC, Pope JC, et al. Use of validated bladder/bowel dysfunction questionnaire in the clinical pediatric urology setting. J Urol 2012;188:1578–83. 10.1016/j.juro.2012.02.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dohil R, Roberts E, Jones KV, et al. Constipation and reversible urinary tract abnormalities. Arch Dis Child 1994;70:56–7. 10.1136/adc.70.1.56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Loening-Baucke V. Urinary incontinence and urinary tract infection and their resolution with treatment of chronic constipation of childhood. Pediatrics 1997;100:228–32. 10.1542/peds.100.2.228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Law E, Yang JH, Coit MH, et al. Toilet school for children with failure to toilet train: comparing a group therapy model with individual treatment. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2016;37:223–30. 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cocchiola MA, Martino GM, Dwyer LJ, et al. Toilet training children with autism and developmental delays: an effective program for school settings. Behav Anal Pract 2012;5:60–4. 10.1007/BF03391824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Luiselli JK. Teaching toilet skills in a public school setting to a child with pervasive developmental disorder. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry 1997;28:163–8. 10.1016/s0005-7916(97)00011-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Toilet training guidelines: day care Providers-The role of the day care provider in toilet training. Pediatrics 1999;103:1367–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]